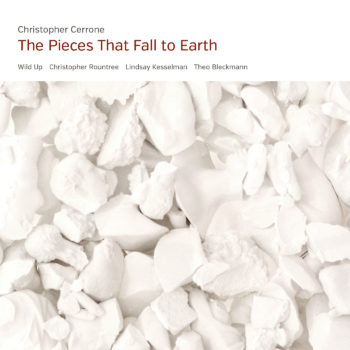

GRAMMY® Nominated for Best Chamber Music/Small Ensemble Performance

Program note by Timo Andres

Christopher Cerrone writes music for human voices which wander and persist through landscapes of cold instrumental sounds. Throughout his vocal works, musical metaphors reinforce poetries of loneliness, alienation, and nostalgia.

To achieve this, Cerrone reorders the typical hierarchy of the classical orchestra. Percussive, quickly-decaying sounds now occupy the core: a pointillistic battery of piano, harp, vibraphone, marimba, and glockenspiel. Stringed instruments are demoted from their central melodic role and leeched of their typical colors, instead concentrating on drones, often using harmonics or alternate bowing techniques. Wind instruments, too, often contribute only un-pitched air, their affect ranging from a subtle atmospheric pressure change to a chuffing engine driving an unstoppable rhythmic machine. In the three pieces on this album, the singer’s part is brought into sharp relief against this background. In contrast to his music for instruments, Cerrone’s writing for the voice could not be more with the grain. The priority here is emotional directness, an urgent—at times, desperate—need to communicate. But this is not the choked, fragmented desperation of so much modernist dramaturgy. Though the severe, crystalline soundscapes of Feldman and Berio are a clear point of reference throughout, it’s the vocal centricity and generosity of bel canto opera that comes through most strongly.

Cerrone’s soloists sing in full sentences, set in strophic, melodically memorable lines. He selects poetry not to deconstruct, but to heighten and concentrate it. Yet at first, the precise relationship between music and text can be difficult to distinguish.These settings don’t cartoon the poems by trying to musically ape their meanings. They strive for something more subtle and difficult, which is to distill meaning into an overall mood or atmosphere. This is necessary given the importance of form in Cerrone’s musical language. The poetic form never guides the setting. Instead, text is repeated as often as necessary to complete the musical arc in a way that satisfies its process.

Take the first, titular song; the text of Kay Ryan’s “The Pieces That Fall to Earth” is set three times, each repetition increasing in volume, intensity, and registral compass. The poetry speaks of random events, and one’s inability to connect these to form predictable patterns. The music, meanwhile, communicates the exact opposite.

The soprano’s melody remains almost the same throughout, set against a stable and inexorable chord progression. Taken together, poetry and music seem to say: the only inevitable thing is randomness, and the constant anticipation of it. At other times, music, text, and form find precise alignment, as in the two rage arias, “That Will to Divest” and “Insult.” Ryan often opens a poem with a declarative, if cryptic, statement—“Action creates / a taste for itself” or “Insult is injury / taken personally”—which the rest of the poem goes on to unpack, resulting in an unexpected moment of clarity at the end. Cerrone’s settings of these two poems mirror each other. There is no harmony here; the musicians violently spit out their words and notes in unison, all while creeping up the chromatic scale a half-step at a time. The songs are timed to end once the soprano can sing no higher. There could hardly be a musically simpler way to treat these settings, and their starkness allows Ryan’s blunt truths to speak all the more forcefully. The final song in Pieces, “The Woman Who Wrote Too Much,” finds the author so deeply embedded in her work that she has literally blinded herself to the realities of life. Cerrone again mirrors music from earlier in the piece—that inevitable chord progression from the first song. Was the writer’s compulsive fate also inevitable from the outset? The ending offers hope, in the form of “dear ones” who break through the narrator’s self-imposed myopia bearing offerings of food. As the final chords build, the sixth scale degree is raised, changing the key but leaving the tonality ambiguous—it could be major or minor, but the music never settles long enough to decide.The singer reaches a frenzy, tripping over her words, and she is violently cut off by scratching strings and blaring trombone. We’re reminded of a line from the second song: “What’s the use / of something / as unstable / and diffuse as / hope—.” The equilibrium between blind searching and sputtering mania proves, in the end, impossible to achieve.

After the coloratura dramatics of Pieces, the compact cycle Naomi Songs explores a different facet of loneliness, probing the wounds of a failed romance. Bill Knott’s poems are temporally surreal—we’re never quite sure what’s taking place in the present, past, or simply inside the poet’s mind. They often seem to be recollected fragments of intimate communication, memories of having shared language with somebody, or even transcended the need for language. Cerrone’s chamber orchestra hugs the contours of the vocal line, surrounding it with a halo of gentle plucks and drones. Register is carefully constrained; even the bass instruments play mostly in their altissimo range, creating a sense of strained, uncomfortable closeness. Only occasionally, in moments of more outward ex- pression, do they drop below the staff to anchor the harmony. The third Naomi song offers a temporary respite from the general sense of anguish; the voice seems momentarily comforted by the presence of a number of electronically-looped doubles, which are in turn echoed by the instruments. As these invented characters multiply, they gently saturate the texture of the music, sustaining all the notes of the Mixolydian scale at once. This warm bath of harmony returns at the very end of the last song, accompanying the realization that the pain will eventually subside and be replaced by openness, even as the emotional wound never fully heals—“a fountain with rooms to let.”

If Pieces and Naomi Songs mostly concern themselves with the subtleties of interior worlds, The Branch Will Not Break turns outward towards nature, landscape, and sweeping gesture. That’s not to say all is well in James Wright’s poems. Time and again, he finds the beauty and purpose of the natural world lacking in himself and anything man-made. The poems often specify their locations—Central Ohio, Rochester, Minnesota, “near the South Dakota border,” William Duffy’s farm—though if he didn’t name them, we’d still recognize their innate Americanness. Shadows of America’s past and future loom over even the most bucolic of these scenes: industrialization, genocide, eventual decay and ruin.

Branch’s form closely mirrors that of Pieces; like the earlier work, its seven songs are arranged in a palindrome, and are fashioned from just four musical motives—an admirable economy. But Branch has its own distinct character and mood. Its closest musical ancestors are the midcentury Americana of Copland and Romanticism of Barber, shot through with the grandeur of early John Adams and repeating variations of Philip Glass—a sturdy formula which is deployed in concentrated bursts.All of Cerrone’s pieces, even purely instrumental ones, have moments where they figuratively burst into song—and Branch is his most melodically effusive. Instead of focussing on the procedural development of harmonic and rhythmic patterns, those patterns (still spinning away in the background) morph into tune after Big Tune. The songs never veer off course into histrionics or kitsch; the structures remain disciplined to the point of severity.Wright’s poems use the first-person perspective, which Cerrone sets for eight-voice chorus—a more appropriate choice than it may initially seem. Wright covers a vast emotional range, from suicidal despair to transcendent joy. At each polarity, the perspective broadens from the concrete world into the metaphysical. The sun and moon take on personified characters imbued with agency—unwanted intruders “pitching into the stove” or illuminating “hills of fresh graves.” Animals, and their feelings, are a recurring motif; Wright identifies with them, but can never measure up (“I feel like half a horse myself”; “A chicken hawk floats over, looking for home. / I have wasted my life”). It makes sense to share these multiple perspectives among multiple singers. Some songs are initiated by soloists (as in the two “Hangovers”) but end up shifting to tutti chorus as Wright’s mind wanders from his body. The last song in the piece, a setting of Wright’s “A Blessing,” concludes with the most potent of these metaphysical moments. At first, the music feels almost naïve; it keeps winding up neatly in C major, phrase after phrase, too sweetly timid to wander far from home. Only on the last lines of the poem—“Suddenly I realize that if I stepped out of my body/ I would break into blossom”—does the harmony pivot around the leading tone, modulating to the opening key of B major. The insistence on C was a setup all along, and the new key feels revelatory, a window thrown open. The chorus now has free reign, repeating the text with jubilant abandon. Even the strings finally join in full force, vaulting above the chorus to play the “I have wasted my life” tune from the first song. As the beginning and end of the piece are musically joined, so are the two poetic extremes; depression and ecstasy are just different settings of the same melody.