Shostakovich on Soviet Party loyalty:

“It is as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, ‘Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing.’”

Shostakovich’s son Maxim said, “My father cried twice in his life: when my mother died and when he came to say they’ve made him join the Party.” Crying is actually an understatement. The man who publicly withstood Stalin’s entire, painful regime finally capitulated to the Party’s pressure in 1960, and he was a sobbing, uncontrollable mess. Then he wrote his 8th String Quartet in only three days.

After writing the quartet, Shostakovich wrote a letter to his friend, confessor Glikman, explaining,

“The title page could carry the dedication: ‘To the memory of the composer of this quartet’ […] while I was composing it I cried as many tears as I would pee after half-a-dozen beers.’”

In this man of paradoxes, one thing is certain: he was not ashamed of life’s rawness. And his music is the same. Rudolf Barshi – a composition student of Shostakovich – and the arranger of the String Quartet No. 8 as the Chamber Symphony, relates stories about Soviet copyists and editors changing Shostakovich’s dissonant, crunchy writing to be less offensive.

Barshai said: “His aim was to demonstrate that ambivalence exists. Wonderful harmony is suddenly interrupted by great discord. He was saying, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, things are not always harmonious. They are hard and tragic too.’”

As a pianist, Shostakovich’s playing was volatile and exhilarating, with fistfuls of wrong notes, tempi that seemed impossible and out of control. The legendary Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter said one time he played a duet with Shostakovich:

“Shostakovich would start at a certain tempo, then get faster or slower. He ignored the pedal completely. And he played incredibly loud all the time […] I was fighting a losing battle.”

Apparently, Richter always had interesting encounters with Shostakovich:

“I was outside the Odessa Opera. It was dusk, and the street lights hadn’t come on. There was a man staring at me. He had white eyes, with no pupils. Suddenly I realized that it was Shostakovich. I went weak at the knees […] I was always ill at ease in his presence. He was very odd: tense, yet extremely refined. A genius, but quite bizarre. A terrible depressive. He was totally crazy too.”

The essence of Shostakovich’s music-making, as composer and performer, was pure vitality, whether slow or fast, major or minor. His music cares not for posterity, only for the moment. And the moment is the only thing this music needs. It whispers and screams: “I am alive! Living hurts bad. It also feels good. Here I am.”

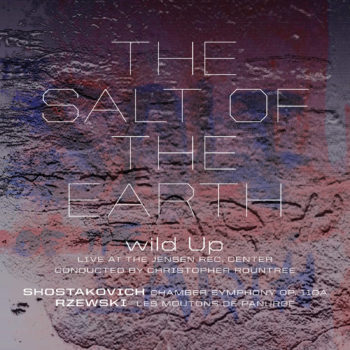

Ironically, the man who never seemed to care one bit about cataloguing and recording his own music has become one of the most recorded twentieth-century composers. So why should we join the ranks and make another recording of an already ultra-famous piece? The same reason anyone goes through the insane amount of time and effort to relive something: there is always more to say.

When we made this recording a couple things happened. The performance felt great. The visceral and emotional energy in the small, packed venue was palpable, and everyone played hard, fast, and beautiful. We assumed the recording would display these things.

But the live recording sounded terrible. To our conservatory-trained ears and minds we heard a slew of mistakes, rough patches, and moments of near collapse. We were confused and worried.

This recording is not edited from that performance. In the process of mixing the raw recording, the goal was to make it more raw, to relive the performance itself by proxy. We weren’t just making a live recording, but making a recording that feels alive. The mistakes we made in the performance are definitely there; in fact, they’re magnified. The bass is loud, the licks are fast, and the chords are crunchy. We hope it hurts good.